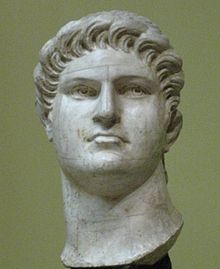

Nero

Great Fire of Rome (64 AD)

Main article: Great Fire of Rome

The Great Fire of Rome erupted on the night of 18 July to 19 July 64. The fire started at the southeastern end of the Circus Maximus in shops selling flammable goods.

Artwork depicting the Great Fire of Rome.

The extent of the fire is uncertain. According to Tacitus, who was nine at the time of the fire, it spread quickly and burned for over five days. It destroyed three of fourteen Roman districts and severely damaged seven. The only other historian who lived through the period and mentioned the fire is Pliny the Elder, who wrote about it in passing. Other historians who lived through the period (including Josephus, Dio Chrysostom, Plutarch and Epictetus) make no mention of it in what remains of their work.

Sketch of Ancient graffiti portrait of Nero found at the Domus Tiberiana.

It is uncertain who or what actually caused the fireâwhether accident or arson. Suetonius and Cassius Dio favor Nero as the arsonist, so he could build a palatial complex. Tacitus mentions that Christians confessed to the crime, but it is not known whether these confessions were induced by torture. However, accidental fires were common in ancient Rome. In fact, Rome suffered other large fires in 69 and in 80.

It was said by Suetonius and Cassius Dio that Nero sang the "Sack of Ilium" in stage costume while the city burned. Popular legend claims that Nero played the fiddle at the time of the fire, an anachronism based merely on the concept of the lyre, a stringed instrument associated with Nero and his performances. (There were no fiddles in 1st-century Rome.) Tacitus's account, however, has Nero in Antium at the time of the fire. Tacitus also said that Nero playing his lyre and singing while the city burned was only rumor.

According to Tacitus, upon hearing news of the fire, Nero returned to Rome to organize a relief effort, which he paid for from his own funds. Nero's contributions to the relief extended to personally taking part in the search for and rescue of victims of the blaze, spending days searching the debris without even his bodyguards. After the fire, Nero opened his palaces to provide shelter for the homeless, and arranged for food supplies to be delivered in order to prevent starvation among the survivors.

In the wake of the fire, he made a new urban development plan. Houses after the fire were spaced out, built in brick, and faced by porticos on wide roads. Nero also built a new palace complex known as the Domus Aurea in an area cleared by the fire. This included lush artificial landscapes and a 30-meter-tall statue of himself, the Colossus of Nero. The size of this complex is debated (from 100 to 300 acres). To find the necessary funds for the reconstruction, tributes were imposed on the provinces of the empire.

Tacitus, in one of the earliest non-Christian references to the origins of Christianity, notes that the population searched for a scapegoat and rumors held Nero responsible. To deflect blame, Nero targeted Christians. He ordered Christians to be thrown to dogs, while others were crucified and burned.

War and peace with Parthia

For more details on this topic, see Roman-Parthian War of 58â63.

Shortly after Nero's accession to the throne in 54, the Roman vassal kingdom of Armenia overthrew their Iberian prince Rhadamistus and he was replaced with the Parthian prince Tiridates. This was seen as a Parthian invasion of Roman territory. There was concern in Rome over how the young Emperor would handle the situation. Nero reacted by immediately sending the military to the region under the command of Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo. The Parthians temporarily relinquished control of Armenia to Rome.

The Parthian Empire c. 60. Nero's peace deal with Parthia was a political victory at home and made him beloved in the east.

The peace did not last and full-scale war broke out in 58. The Parthian king Vologases I refused to remove his brother Tiridates from Armenia. The Parthians began a full-scale invasion of the Armenian kingdom. Commander Corbulo responded and repelled most of the Parthian army that same year. Tiridates retreated and Rome again controlled most of Armenia.

Nero was acclaimed in public for this initial victory. Tigranes, a Cappadocian noble raised in Rome, was installed by Nero as the new ruler of Armenia. Corbulo was appointed governor of Syria as a reward.

In 62, Tigranes invaded the Parthian province of Adiabene. Again, Rome and Parthia were at war and this continued until 63. Parthia began building up for a strike against the Roman province of Syria. Corbulo tried to convince Nero to continue the war, but Nero opted for a peace deal instead. There was anxiety in Rome about eastern grain supplies and a budget deficit.

The result was a deal where Tiridates again became the Armenian king, but was crowned in Rome by Emperor Nero. In the future, the king of Armenia was to be a Parthian prince, but his appointment required approval from the Romans. Tiridates was forced to come to Rome and partake in ceremonies meant to display Roman dominance.

This peace deal of 63 was a considerable victory for Nero politically. Nero became very popular in the eastern provinces of Rome and with the Parthians as well. The peace between Parthia and Rome lasted 50 years until Emperor Trajan of Rome invaded Armenia in 114.

Other major power struggles and rebellions

A plaster bust of Nero, Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

The war with Parthia was not Nero's only major war but he was both criticized and praised for an aversion to battle. Like many emperors, Nero faced a number of rebellions and power struggles within the empire.

British Revolt of 60â61 (Boudica's Uprising)

Further information: Boudica § Boudica's Uprising

In 60, a major rebellion broke out in the province of Britannia. While the governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and his troops were busy capturing the island of Mona (Anglesey) from the druids, the tribes of the southeast staged a revolt led by queen Boudica of the Iceni. Boudica and her troops destroyed three cities before the army of Paulinus could return, receive reinforcements, and quell the rebellion in 61. Fearing Paulinus himself would provoke further rebellion, Nero replaced him with the more passive Publius Petronius Turpilianus.

The Pisonian Conspiracy of 65

Main article: Pisonian conspiracy

In 65, Gaius Calpurnius Piso, a Roman statesman, organized a conspiracy against Nero with the help of Subrius Flavus and Sulpicius Asper, a tribune and a centurion of the Praetorian Guard. According to Tacitus, many conspirators wished to "rescue the state" from the emperor and restore the Republic. The freedman Milichus discovered the conspiracy and reported it to Nero's secretary, Epaphroditos. As a result, the conspiracy failed and its members were executed including Lucan, the poet. Nero's previous advisor, Seneca was ordered to commit suicide after admitting he discussed the plot with the conspirators.

The First Jewish War of 66â70

Main article: First Jewish-Roman War

In 66, there was a Jewish revolt in Judea stemming from Greek and Jewish religious tension. In 67, Nero dispatched Vespasian to restore order. This revolt was eventually put down in 70, after Nero's death. This revolt is famous for Romans breaching the walls of Jerusalem and destroying the Second Temple of Jerusalem.

The revolt of Vindex and Galba and the death of Nero

Nero, Sestertius with countermark "X" of Legio X Gemina.

Obv: Laureate bust right.

Rev: Nero riding horse right, holding spear, DECVRSIO in exergue; S C across fields.

A marble bust of Nero, Antiquarium of the Palatine.

In March 68, Gaius Julius Vindex, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, rebelled against Nero's tax policies. Lucius Verginius Rufus, the governor of Germania Superior, was ordered to put down Vindex's rebellion. In an attempt to gain support from outside his own province, Vindex called upon Servius Sulpicius Galba, the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, to join the rebellion and further, to declare himself emperor in opposition to Nero.

At the Battle of Vesontio in May 68, Verginius' forces easily defeated those of Vindex and the latter committed suicide. However, after putting down this one rebel, Verginius' legions attempted to proclaim their own commander as Emperor. Verginius refused to act against Nero, but the discontent of the legions of Germany and the continued opposition of Galba in Spain did not bode well for him.

While Nero had retained some control of the situation, support for Galba increased despite his being officially declared a public enemy. The prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Gaius Nymphidius Sabinus, also abandoned his allegiance to the Emperor and came out in support for Galba.

In response, Nero fled Rome with the intention of going to the port of Ostia and, from there, to take a fleet to one of the still-loyal eastern provinces. According to Suetonius, Nero abandoned the idea when some army officers openly refused to obey his commands, responding with a line from Vergil's Aeneid: "Is it so dreadful a thing then to die?" Nero then toyed with the idea of fleeing to Parthia, throwing himself upon the mercy of Galba, or to appeal to the people and beg them to pardon him for his past offences "and if he could not soften their hearts, to entreat them at least to allow him the prefecture of Egypt". Suetonius reports that the text of this speech was later found in Nero's writing desk, but that he dared not give it from fear of being torn to pieces before he could reach the Forum.

Nero returned to Rome and spent the evening in the palace. After sleeping, he awoke at about midnight to find the palace guard had left. Dispatching messages to his friends' palace chambers for them to come, he received no answers. Upon going to their chambers personally, he found them all abandoned. When he called for a gladiator or anyone else adept with a sword to kill him, no one appeared. He cried, "Have I neither friend nor foe?" and ran out as if to throw himself into the Tiber.

Returning, Nero sought for some place where he could hide and collect his thoughts. An imperial freedman, Phaon, offered his villa, located 4 miles outside the city. Travelling in disguise, Nero and four loyal

freedman, Epaphroditos, Phaon, Neophytus, and Sporus, reached the villa, where Nero ordered them to dig a grave for him.

At this time, a courier arrived with a report that the Senate had declared Nero a public enemy and that it was their intention to execute him by beating him to death and that armed men had been sent to apprehend him for the act to take place in the Forum. The Senate actually was still reluctant and deliberating on the right course of action as Nero was the last member of the Julio-Claudian Family. Indeed, most of the senators had served the imperial family all their lives and felt a sense of loyalty to the deified bloodline, if not to Nero himself. The men actually had the goal of returning Nero back to the Senate, where the Senate hoped to work out a compromise with the rebelling governors that would preserve Nero's life, so that at least a future heir to the dynasty could be produced.

Nero, however, did not know this, and at the news brought by the courier, he prepared himself for suicide, pacing up and down muttering "Qualis artifex pereo" which translates to English as "What an artist dies in me." Losing his nerve, he first begged for one of his companions to set an example by first killing himself. At last, the sound of approaching horsemen drove Nero to face the end. However, he still could not bring himself to take his own life but instead he forced his private secretary, Epaphroditos, to perform the task.

When one of the horsemen entered, upon his seeing Nero all but dead he attempted to stop the bleeding in vain. Nero's final words were "Too late! This is fidelity!" He died on 9 June 68, the anniversary of the death of Octavia, and was buried in the Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, in what is now the Villa Borghese (Pincian Hill) area of Rome.

With his death, the Julio-Claudian dynasty ended. The Senate, when news of his death reached Rome, posthumously declared Nero a public enemy to appease the coming Galba (The Senate had initially declared Galba as a public enemy) and proclaimed him the new emperor. Chaos would ensue in the year of the Four Emperors.

Post mortem

See also: Nero Redivivus legend and Pseudo-Nero

The alleged Tomb of Nero.

According to Suetonius and Cassius Dio, the people of Rome celebrated the death of Nero. Tacitus, though, describes a more complicated political environment. Tacitus mentions that Nero's death was welcomed by Senators, nobility and the upper class. The lower-class, slaves, frequenters of the arena and the theater, and "those who were supported by the famous excesses of Nero", on the other hand, were upset with the news. Members of the military were said to have mixed feelings, as they had allegiance to Nero, but were bribed to overthrow him.

Eastern sources, namely Philostratus II and Apollonius of Tyana, mention that Nero's death was mourned as he "restored the liberties of Hellas with a wisdom and moderation quite alien to his character" and that he "held our liberties in his hand and respected them."

Modern scholarship generally holds that, while the Senate and more well-off individuals welcomed Nero's death, the general populace was "loyal to the end and beyond, for Otho and Vitellius both thought it worthwhile to appeal to their nostalgia."

Nero's name was erased from some monuments, in what Edward Champlin regards as an "outburst of private zeal". Many portraits of

Nero were reworked to represent other figures; according to Eric R. Varner, over fifty such images survive. This reworking of images is often explained as part of the way in which the memory of disgraced emperors was condemned posthumously (see damnatio memoriae). Champlin, however, doubts that the practice is necessarily negative and notes that some continued to create images of Nero long after his death.

Apotheosis of Nero, c. after 68. Artwork portraying Nero rising to divine status after his death.

The civil war during the year of the Four Emperors was described by ancient historians as a troubling period. According to Tacitus, this instability was rooted in the fact that emperors could no longer rely on the perceived legitimacy of the imperial bloodline, as Nero and those before him could. Galba began his short reign with the execution of many allies of Nero and possible future enemies. One such notable enemy included Nymphidius Sabinus, who claimed to be the son of Emperor Caligula.

Otho overthrew Galba. Otho was said to be liked by many soldiers because he had been a friend of Nero's and resembled him somewhat in temperament. It was said that the common Roman hailed Otho as Nero himself. Otho used "Nero" as a surname and reerected many statues to Nero. Vitellius overthrew Otho. Vitellius began his reign with a large funeral for Nero complete with songs written by Nero.

After Nero's suicide in 68, there was a widespread belief, especially in the eastern provinces, that he was not dead and somehow would return. This belief came to be known as the Nero Redivivus Legend.

The legend of Nero's return lasted for hundreds of years after Nero's death. Augustine of Hippo wrote of the legend as a popular belief in 422.

At least three Nero imposters emerged leading rebellions. The first, who sang and played the cithara or lyre and whose face was similar to that of the dead emperor, appeared in 69 during the reign of Vitellius. After persuading some to recognize him, he was captured and executed. Sometime during the reign of Titus (79â81), another impostor appeared in Asia and sang to the accompaniment of the lyre and looked like Nero but he, too, was killed.Twenty years after Nero's

death, during the reign of Domitian, there was a third pretender. He was supported by the Parthians, who only reluctantly gave him up, and the matter almost came to war.

Physical appearance

In his book The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Suetonius describes Nero as "about the average height, his body marked with spots and malodorous, his hair light blond, his features regular rather than attractive, his eyes blue and somewhat weak, his neck over thick, his belly prominent, and his legs very slender."

Reputed martyrdoms of Peter and Paul

The first text to suggest that Nero ordered the execution of an apostle is the apocryphal Ascension of Isaiah, a Christian writing from the 2nd century. It says, the slayer of his mother, who himself (even) this king, will persecute the plant which the Twelve Apostles of the Beloved have planted. Of the Twelve one will be delivered into his hands.

Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 275â339) was the first to write

explicitly that Paul was beheaded in Rome during the reign of Nero. He states that Nero's persecution led to Peter and Paul's deaths, but that Nero did not give any specific orders. However, several other accounts going back to the 1st century have Paul surviving his two years in Rome and travelling to Hispania, before facing trial in Rome again prior to his death.

Peter is first said to have been crucified upside-down in Rome during Nero's reign (but not by Nero) in the apocryphal Acts of Peter (c. 200). The account ends with Paul still alive and Nero abiding by God's command not to persecute any more Christians.

By the 4th century, a number of writers were stating that Nero killed Peter and Paul.

Wikipedia